In the 21st century, we have developed a new lexicon of ‘digital disruption’. Any company that innovates is ‘changing the game’, new ideas are ‘revolutionary’, and most of all, start-ups that make a dent in the market must be ‘disruptive’.

In truth, few companies are worthy of these monikers. To disrupt an industry means to deliver on consumer desires with a business model that displaces the incumbents, creating an almost unfair competitive advantage.

Spotify, the digital audio streaming service, meets these criteria. At a time when people were listening to more music than ever, but record labels were struggling financially, Spotify decided to lean into those consumer trends rather than trying to counteract them.

People simply didn’t want to buy individual albums or songs any more. Many were willing to use music piracy services to access the content on their terms, rather than continue paying for CD’s.

Spotify offered a freemium, all-you-can-eat (or, listen) model, mobile access, personalized playlists, and even music downloads to listen to offline. Free users hear ads between songs, while paid subscribers can access over 50 million titles, ad-free.

Artists are paid commissions based on the popularity of their songs, which is in theory a democratic way of distributing the subscription and advertiser revenues. This also extends the lifespan of their earning potential, as streaming is a never-ending process. An album is bought once, but its songs are listened to for years. The Spotify model rewards this repeat listening.

Today, Spotify has over 250 million users, including over 100 million paid subscribers across more than 70 countries. For many, the brand name Spotify is synonymous with music streaming. In fact, if you type ‘playlist.new’ into the Google Chrome browser address bar, it will take you to the Spotify website.

In 2020, Spotify will continue its push into podcast publishing and will open up a new suite of audio tools for advertisers. The future looks bright green, indeed.

It’s not all glory, of course. Any company that provides inventive new answers to age-old questions will always create a new set of questions in its wake. Spotify is not the only company vying to create these solutions and its competitors include Google, Amazon, and Apple.

This is the story of a genuinely disruptive business that has, better than just about anyone else, delivered on the notion that data and creativity are mutually reinforcing concepts.

The Spotify History

Spotify’s co-founders, Daniel Ek and Martin Lorentzon, set up the company in Stockholm in 2006. The name ‘Spotify’ is essentially the result of a misunderstanding. Lorentz made a suggestion for a company name, which was misheard as ‘Spotify’ by Ek.

The pair later decided this could be a fitting portmanteau of ‘spot’ and ‘identify’. And lo, Spotify came to be.

The initial Spotify product launched in 2008, starting off as an ‘invitation only’ service.

At this stage, the company was still trying to reach agreements with major music labels, but the extensive vision for the company’s potential was already evident. As Daniel Ek (now the company’s CEO) noted, “People just want to have access to all of the world’s music”, and that’s precisely what Spotify aimed to provide.

Spotify launched in the UK in 2009, the company’s first foray into an international market, followed soon by France and Spain. Way back then, the options for open access to music were either limited, expensive, or illegal.

Spotify’s value proposition was clear, appealing, and refreshing. It felt almost too good to be true; unlimited music, from all artists, for free. Users just had to put up with occasional ad breaks, nothing more.

The UK launch was so popular that Spotify had to go back to invitation-only access to manage the demand.

Daniel Ek and Martin Lorentzon both have a background in the digital advertising industry (most notably, at TradeDoubler) and their initial plan was to generate revenue by monetizing user attention through ad spots between songs.

The service launched in more countries, including the US in 2011, then in a variety of European, Latin American, and Asian markets.

Throughout this period of massive growth, Spotify saw the possibility for paid subscriptions to deliver recurring, reliable revenue streams.

Users were willing to pay $10 per month to avoid the ads altogether. This helped tie users to the platform and generate that most precious of modern commodities: behavioral data.

Spotify continued to add new, customer-pleasing features, such as the Spotify Lite app for Android that provides mobile access to the platform without using a huge amount of mobile data. This app is available in 36 countries today and has been a significant factor in Spotify’s success in Latin America and Asia.

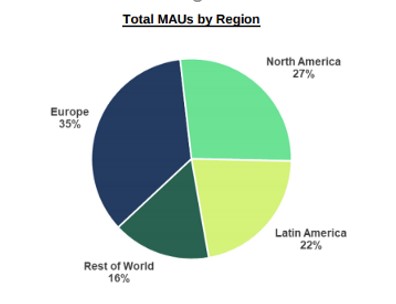

While Europe remains its biggest region in terms of user volume, North America is close behind and Latin America is growing quickly, as seen in the chart of monthly active users (MAUs) below.

In keeping with its company ethos, Spotify took an inventive, democratic approach to its Initial Public Offering (IPO) on Wall Street in April 2018. Instead of selling the first allocation of shares to Wall Street leaders and allowing them to set the benchmark price, Spotify opted for a ‘direct listing’. This meant they posted the available shares on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) and left it to the market to arrive at a fair price. Industry insiders anticipated a rocky ride for Spotify’s share price, but the prices remained relatively stable for the first six months.

In Spotify’s application to list on the NYSE, they summarized their ambitions as follows:

“Our mission is to unlock the potential of human creativity by giving a million creative artists the opportunity to live off their art and billions of fans the opportunity to enjoy and be inspired by these creators.”

The crucial element that has allowed Spotify to create these connections is the vast quantity of data created by both artists and fans on the platform.

Discover Weekly and Spotify’s Data Advantage

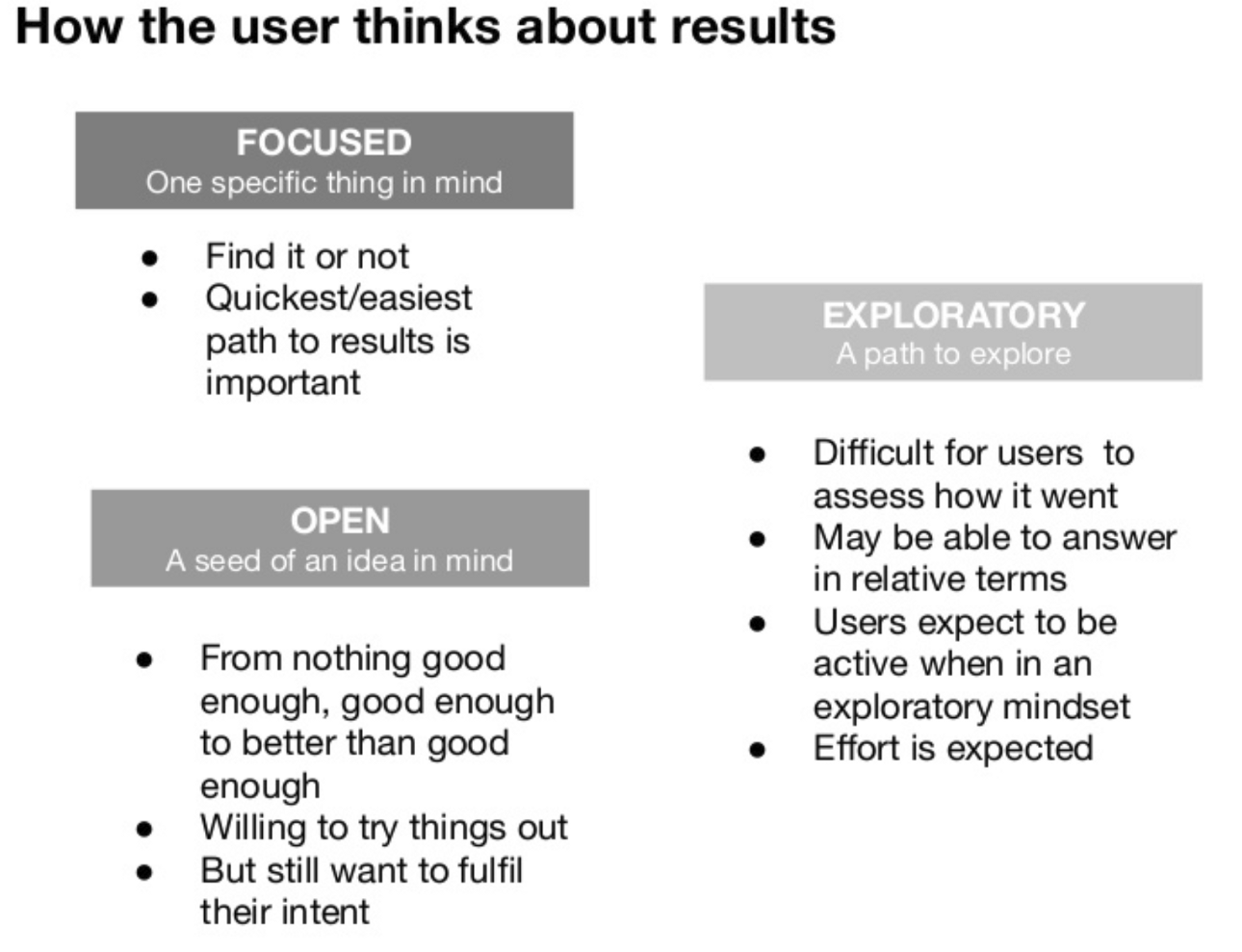

Spotify estimates that 60% of the time listeners are in a ‘closed’ mindset when they are on the app; they know what they want to listen to and they just need to find it.

The remaining 40% of time is spent in an ‘open’ mindset.

In this mindset, users put in less effort, they scroll less, they skip tracks more often, and they click less on the artist for further information.

Essentially, they are receptive to new ideas, but in a passive yet impatient state.

Spotify caters to that 60% ‘closed’ mindset in spectacular fashion. With over 50 million songs and 500,000 podcasts currently available, it is likely that users can find whatever track or podcast they have in mind.

However, that competitive advantage can be copied. Another company with deeper pockets (say, Apple or Amazon) could secure the same rights and offer a cheaper monthly subscription. In a race to the bottom, even a company as big as Spotify will lose to these giants.

Spotify has, however, used data to cater to that 40% ‘open’ mindset in a variety of increasingly impressive ways.

The core driver of its addictive appeal is the Spotify recommender system, which keeps the stream flowing long after the user’s selected tracks have finished.

The company’s data scientists knew that every time a user selects or skips a track, they create a data point. These data points tell Spotify something about each individual’s preferences.

If Spotify could combine this with a mathematical understanding of musical genres and artists, they could start to match user tastes with new music. That would keep them listening to Spotify and, crucially, would decrease the likelihood of switching to a rival platform.

In essence, Spotify could be that cool friend that suggests those cult records and B-sides you’d love, if you only knew how to find them. Competitors like US-based Pandora used manual tagging to categorize songs and artists, but Spotify figured it could use Machine Learning to automate and scale this laborious process. In fact, Machine Learning could also find hidden patterns that link musical genres, creating recommendations that no human curator would think to identify.

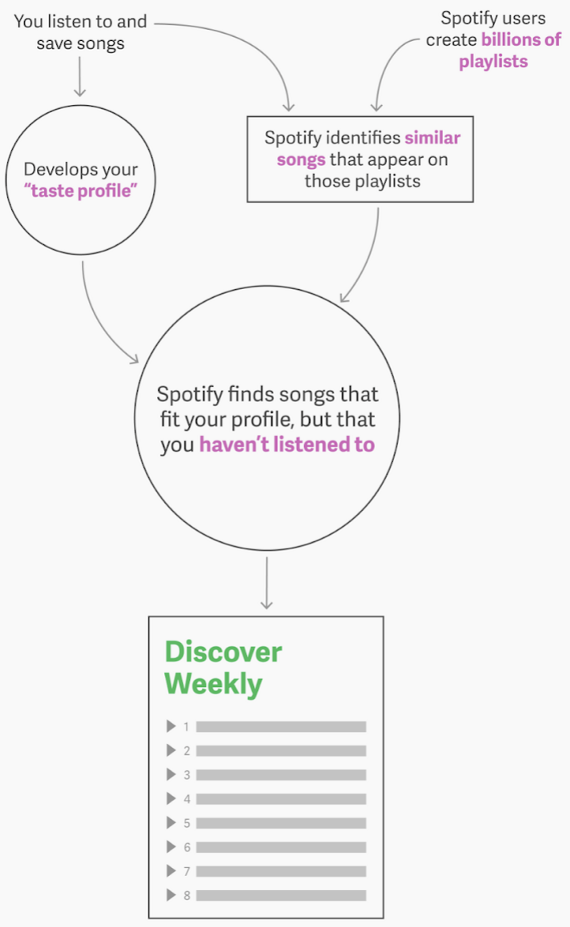

This insight was converted into a highly-successful product, in the form of the Discover Weekly playlists. If ‘free access to all the world’s music’ was Spotify’s marquee introduction to the market, this personalized approach to music curation took the company to the next level.

After all, with choice comes complexity. Discover Weekly removes this paralysis by delivering a new list of 30 songs to each user’s account each Monday, based on their unique taste profile. The process looks a little like this:

Each user has a ‘taste profile’ and, although we cannot access these through the interface, Spotify did provide one Quartz journalist with a glimpse at theirs:

Discover Weekly has been a phenomenal success for Spotify; over 5 billion tracks were streamed through these playlists in the first year after launch.

This also allows Spotify to surface the ‘long tail’ of artists and songs that may otherwise go unheard. It is a similar model to Amazon’s “Recommended for You” section, or Netflix’s “Top Picks”.

This can be great for artists, too, as it gives them another avenue towards money-spinning song listens. Calling it ‘money-spinning’ might be a stretch; even though Spotify has paid out over $13 billion in royalties, it pays artists between $0.006 and $0.0084 per play.

Some enterprising musicians have tried to game this system by creating short songs with keyword-optimized titles, to increase their likelihood of being played often.

At the opposite end of the spectrum, Taylor Swift removed her albums from the platform in 2014 in protest at the lack of remuneration received by musicians. She has since returned to Spotify, but artists still claim they make four times more from Apple Music for streams of their songs.

This points to the fact that Spotify’s advantages have always truly resided in their understanding of consumer trends, and their use of data and technology to deliver on these demands. This can then be used as leverage to convince artists to share their wares on the platform; they will go where their audience is, naturally.

In particular, Spotify has shown other brands how to create data-driven marketing, without being creepy or boring.

Spotify’s Marketing Strategy

Every company today claims that their digital marketing is data-driven. This is the same as companies claiming to be customer-centric because they consider the customer in their strategy. Of course they do; without customers, they wouldn’t be in business. However, to be customer-centric is different than being merely customer-focused.

Inevitably, any company’s digital marketing is influenced by data. Very few marketers fly blind into their ad platforms, ready to blow the year’s budget on unsubstantiated hunches. However, grabbing a few metrics from Google Analytics or Facebook doesn’t constitute being ‘data-driven’, either.

Spotify showed us all how to use big data with a deft touch in its out-of-home campaigns from 2017 and 2018.

It took data points from its users’ listening habits to create humorous billboards, localized to a selection of large cities.

This example from New York played on the popularity of the Hamilton musical, but mainly made headlines for the adjoining creative, “Dear person who played “Sorry” 42 times on Valentine’s Day. What did you do?”

By addressing these to a specific user (without naming them, of course), Spotify let its audience in on its data capturing prowess. This could so easily fall into the trap of being creepy, as Spotify’s imitators have found.

Digital bank Revolut got it all wrong in 2018 by applying the exact same structure, without the good-natured humor. The difference between the two lies in the type of data used, but also in the human element of the creative delivery. Revolut received a lot of press for this one, but mainly because its ads were deemed ‘creepy’ and ‘invasive’.

Spotify has continued to use social media tropes to add color to its data-driven approach, in these 2018 billboards:

And also the local angle, as in these advertisements in Manchester city center in 2019:

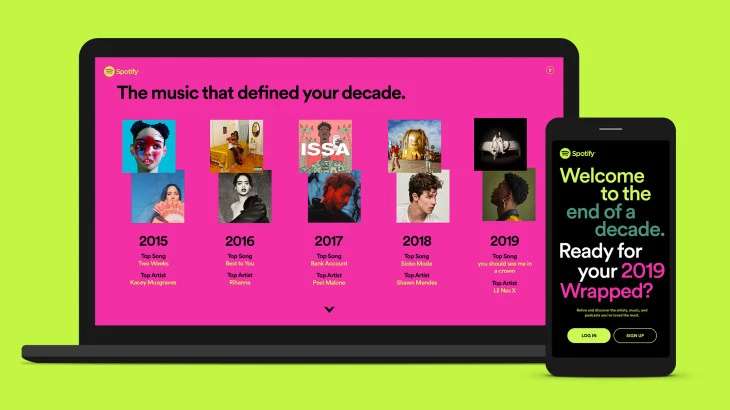

These campaigns get people talking, which extends their reach and longevity. In a similar vein, Spotify collates a personalized review of the year for each user, showing them their favorite artists and how these compare to the preferences of their peers.

Spotify grew initially based on word-of-mouth recommendations. Today, it uses data to create content that its subscribers will want to share. Listeners become brand ambassadors, often without even realizing it.

We read about these best practices online and in books, but their execution is deceptively challenging. Spotify demonstrates how to deliver customer-centric marketing that gets results, using hard data with a soft touch.

What Does the Future Hold for Spotify

Spotify has targeted podcasts and original content as two core growth drivers in the coming years.

It has overtaken Apple as the top podcasting platform, but it still reaches just 14% of its total user base with spoken-word content.

However, this is a core area of focus and the company’s CEO Daniel Ek said, “We believe monetization of podcasts remains a huge opportunity, and it is something that we’re going to start looking at in 2020,” in its Q3 2019 earnings call. By the end of 2020, Spotify wants podcasts to account for 20% of overall listening time on the platform.

As such, it was no surprise to see Spotify announce its new Spotify Podcast Ads product in January 2020.

This new Streaming Ad Insertion (SAI) system will collect data on how many impressions its ads create, their frequency, and their reach. The tool will also capture anonymized user device, age, and gender information. Advertisers will now be able to approach podcast advertising with the same tools they expect as standard for search advertising or paid social.

There is a catch, however; Streaming Ad Insertion is only available for shows that are either produced by Spotify or exclusive to the platform. Shows rumored to be in development at time of writing include a daily sports news round-up and original drama series. This is a marked shift for Spotify, turning it into a content creator as well as platform owner.

Spotify only launched in India in 2019 and will certainly hope to make further inroads in such an important market during 2020, while also continuing its development in Latin America and Africa. It has overtaken Pandora as the most popular digital audio streaming service in the US and will hope to cement its dominance in Europe.

As Daniel Ek has noted, Spotify is just a platform.

There is no reason its ambitions should be restricted to music – or even to podcasts. As user preferences continue to point to video consumption, we will see Spotify gravitate to that medium. The competition is fierce, but Spotify delivers on customer demands better than anyone.

We should expect them to shape our media consumption habits for many years to come.